Rebuilding speech with help from artificial intelligence

An artist’s impression of artificial intelligence. Hong Kong researchers are using AI to help people with dysarthria communicate.Credit: Yuichiro Chino/Moment/Getty

Speech conveys who we are, what we think, and what we need. However, the ability to communicate can be compromised by neural and muscle damage, leading to a condition called dysarthria, which causes speech to become slow, slurred and hard to understand.

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning have the potential to help people with dysarthria overcome these barriers to communication.

“With the advanced tools developed in our research laboratory, computers are capable of recognizing the unclear speech of patients with dysarthria and converting it to intelligible speech, facilitating and enhancing communication,” says Helen Meng, a professor of systems engineering and engineering management at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

Beyond English

Meng joined CUHK in 1998, after receiving degrees in electrical engineering and computer science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. At CUHK, she soon established the Human-Computer Communications Laboratory, which focuses on speech and language processing. The laboratory grew into a CUHK-led ‘InnoHK Centre’ called the Centre for Perceptual and Interactive Intelligence, where Meng is now director.

One of Meng’s research projects focuses on using computational and machine learning techniques to decode and reconstruct spoken languages. She puts a particular emphasis on impaired speech for languages other than English, including tonal languages such as Chinese, which also has multiple dialects. That’s important, says Meng, because robust algorithms that adapt to different languages are essential for ensuring everyone has access to future technological advances.

One example of the approaches from Meng’s team in developing inclusive technologies is their advanced AI technology for dysarthric speech reconstruction (DSR) for speakers of both English and Cantonese, a Chinese dialect common in Hong Kong and southern China.In Meng’s system, dysarthric speech is fed into an AI-driven ‘encoder’ which extracts features from the raw speech and translates them into latent features. These are then analysed by further AI algorithms and used to generate clearer speech through a synthesizer. Improving the ease with which people with speech disorders communicate is important for social inclusion, says Meng.

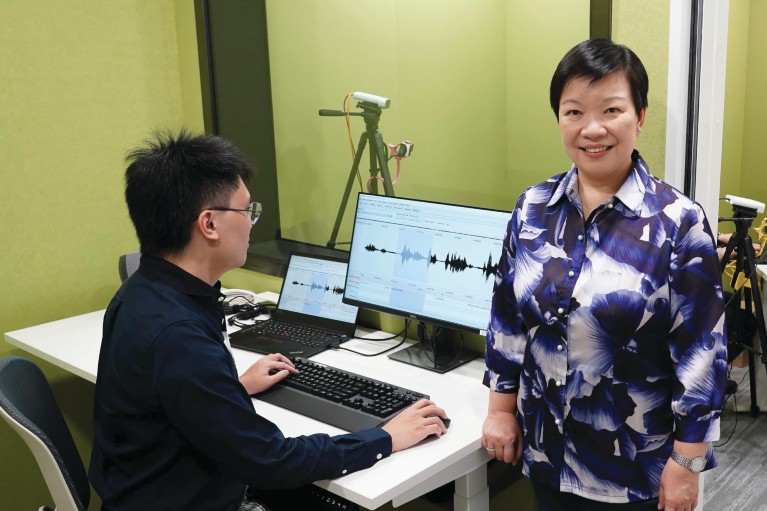

Helen Meng (at right) with the team’s IT manager William Leung — both of the Chinese University of Hong Kong — employ technology solutions to reconstruct Cantonese dysarthric speech.

To achieve their goals, Meng’s team has had to overcome several challenges. For example, publicly available datasets of disordered speech are mostly in English, and hence only suitable for training AI speech processing models in that language.

To address this issue, Meng is creating the Chinese University Dysarthria Corpus or CUDYS, which will contain speech data from Cantonese speakers with dysarthria. Dysarthric Cantonese speakers are asked to produce recordings of a sufficient level of clarity for it to be useful for machine learning. This is exhausting for someone with dysarthria, says Meng.

The team is now using this data to develop AI-based tools to reconstruct Cantonese dysarthric speech to produce more normal-sounding speech. The tools are based on advanced modeling techniques used in English dysarthric speech that the team have adapted for Cantonese1.

Natural speech

So far, the team’s AI-based DSR approach has achieved roughly a 30% reduction in errors in machine recognition compared to the original dysarthric speech. This reflects an enhancement in terms of intelligibility, as well as naturalness, of the reconstructed speech, says Meng2.

To enhance AI training and further improve the restored language, the team is now using self-supervised speech representation learning and discrete speech units, reducing word error rates still more. The enhanced training system is also less susceptible to background noise and different speaking rates3.

Key to CUHK’s success, says Meng, is their emphasis on understanding the acoustic-phonetic characteristics of dysarthria. For example, in dysarthria, reduced muscular control of speech organs, such as the tongue and jaw, leads to imprecise pronunciations. So, the team selected 20 distinctive vocal features that adequately represent the different aspects of muscle control.

Analysis based on this feature set is providing insights into how dysarthric speech differs from regular speech and is being used to develop more effective speech therapy techniques as well as AI-driven communication aids4.

Meng’s team also see another potential use for their voice analysis systems. “Voice is an inexpensive, easily acquired biomarker that can be used for detecting and monitoring problems related to dementia,” explains Meng.

The team is developing a screening and monitoring platform that uses AI to extract markers of neurological disease from spoken languages5. These markers include lack of fluency, hesitation and ‘filler pauses’, where a sound — such as ‘um’ — is used as a pause in speech.

The platform has shown its potential mettle for detecting Alzheimer’s against a publicly available benchmark dataset known as the ADReSS corpus, says Meng.

More than voice

In their other projects, Meng’s colleagues are working on neurological disease markers for speakers of English, Cantonese and Mandarin; and a research technique for analysing brain activity via MRI signals of people engaging in speech perception.

As to what motivates Meng to help people to better use language to convey who they are, what they think, and what they need — that’s simple. “The well-being of the community motivates our research,” she says.

Source link